Driving both the exhibitions and the educational content of this website are four Easter Island myths: the myth of creation, the myth of movement, the myth of power, and the myth of presence. There is at least one of these myths contained in every example in popular culture in which the moai have been depicted. These myths are fictitious accounts or stories that have imagined explanations for the perceived riddles of the moai. However, the moai are not alone when considering the myths of Easter Island, with popular culture also drawn to the myths that surround rongorongo, Makemake, moai kavakava, and the birdman cult. A focus of the exhibitions has been an attempt to understand the ways in which these myths operate. This extends into this website and, as it develops, projects for educational use will be featured below and will work in conjunction with the Popular Culture page.

The Moai and the Myth of Creation

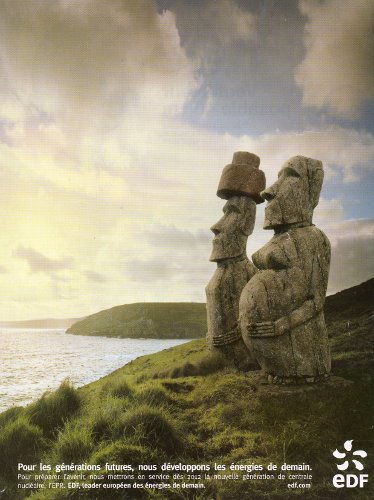

EDF nuclear energy, French magazine advert, 2008 |

|

Easter Island is, geographically, very isolated from the rest of the world. Its remoteness from the main sources of mass culture and popular interest in the moai - Western Europe, Japan, and the USA - has encouraged the myths. Also, many aspects of the island's history continue to be debated and theorised, allowing for alternative ideas to be proposed.

Ian Conrich Jump to contents |

The Moai and the Myth of Movement

Keroro Gunsou (Sgt. Frog), Japanese animation

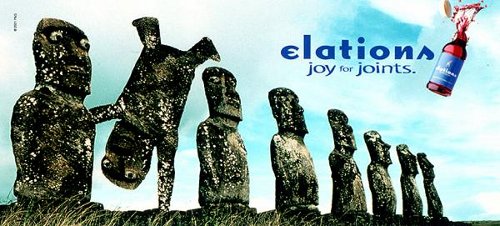

Elations dietary supplements, US magazine advert, 2001

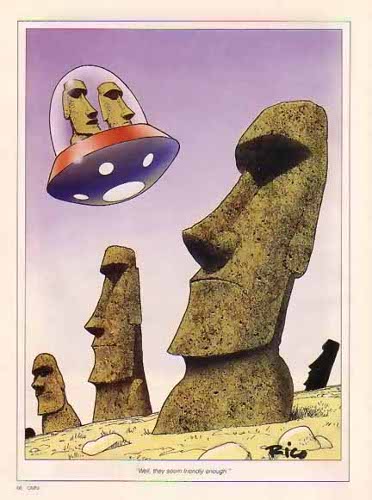

There is a popular myth that the moai are able to come alive: that they can walk, talk, see, and hear. The humanisation of the moai has been aided by mythical accounts that present the island as uninhabited and abandoned. The human-looking moai fill the gap that remains once the native population has been removed. Furthermore, fantasies that present the moai as from another world, or belonging to a mysterious and forgotten civilisation, play with notions of the stone figures slumbering, frozen in time and waiting for the moment in which they will be required to awaken. Their lack of animation lends them to the myth that they can be animated with their subsequent behaviour tending to involve one of two extremes: humour or aggression.

Ian Conrich Jump to contents |

The Moai and the Myth of Power

Monster Maulers (aka Kyukyoku Sentai Dadandam) fighting genre computer game, by Konami, 1993

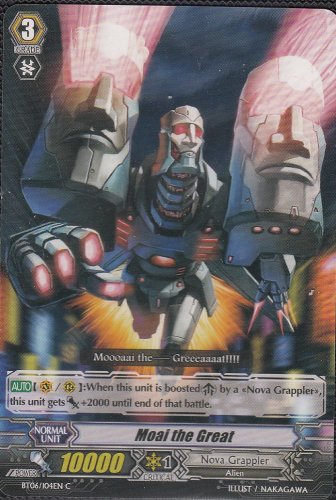

Moai the Great, Cardfight!! Vanguard trading card game, volume 6 |

|

The presence of such monolithic structures, and the ability for them to even be moved and erected has led to a myth of power, whereby whoever created the moai must have been of incredible strength. The moai are said to have 'walked' to their positions, but in some fiction it is proposed that they flew, with an ariki (an Easter Island great chief) exhibiting the controlling power. In popular fiction, the ariki can be distorted and become an excuse for introducing wizards or witches to the stories. Corruption tends to follow, with the discovery of the source of this strength - found within the island - presenting huge power to mere humans.

Ian Conrich Jump to contents |

The Moai and the Myth of Presence

Inflatable moai, Toronto

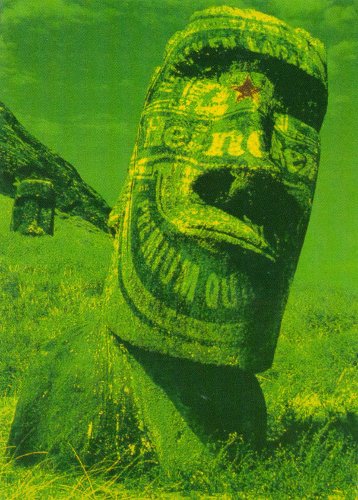

Hong Kong advertising postcard for Heineken Lager, 1998 |

|

The iconic form of the moai has inspired many fantasies where they are imagined emerging elsewhere. The moai are so heavy, so far away, and so difficult to transport, that there is in foreign cultures a popular appeal in placing versions in alternative environments nearer to home, partly as a desire perhaps to possess or transfer their mystique. Similarly, there is a powerful effect in placing different carvings in the spaces next to the moai on the island, or remodelling the moai to incorporate a new design. In fact, these stone giants are so prominent and such an essential aspect of Easter Island's geography, that to have them reconfigured, replaced, or re-emerge elsewhere, can create disorder, irony, or surprise.

Ian Conrich Jump to contents |

The Rongorongo Tablets

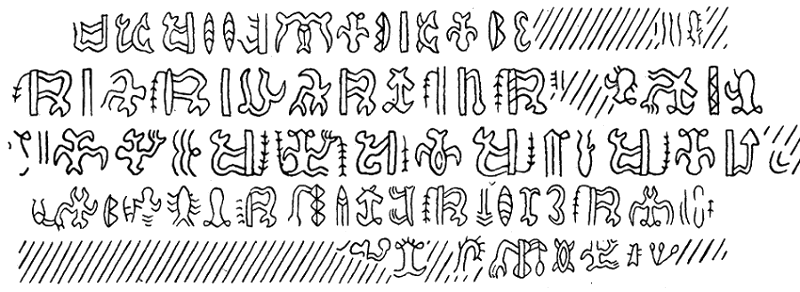

Sketch showing the glyphs on side B of the rongorongo tablet known as the 'London tablet' after its location - the British Museum, London. Note the writing direction, with every other line upside down. |

|

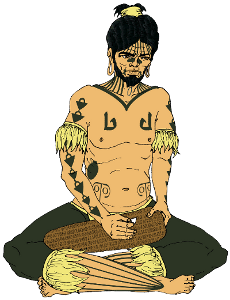

A concept of a rongorongo scribe based on reports made by early visitors to Easter Island. The outline of the glyphs was done first with a piece of obsidian (volcanic glass). Afterwards, a shark's tooth was used to make the outline more distinct. Some tablets are 'fluted' meaning that channels were carved in to the wooden surface before the glyphs were carved, possibly to protect the inscription from surface damage, or one theory is that the scribes were mimicking the structure of the banana leaf, which they may have used for practice. Illustration © Martyn Harris, 2010.

Another part of the extraordinary history of Easter Island, are the rongorongo inscriptions, of which only 26 tablets and artefacts exist since many were destroyed through war and fire. They are now scattered around the world's museums and archives, and nearly 150 years since their discovery they remain undeciphered. Significantly, the islanders are the only Polynesian group to have possessed a written language before the arrival of the missionaries. The term rongorongo possibly comes from te kohau rongorongo, meaning 'the stick of the rongorongo men', although there is still some debate.

Martyn Harris Jump to contents |

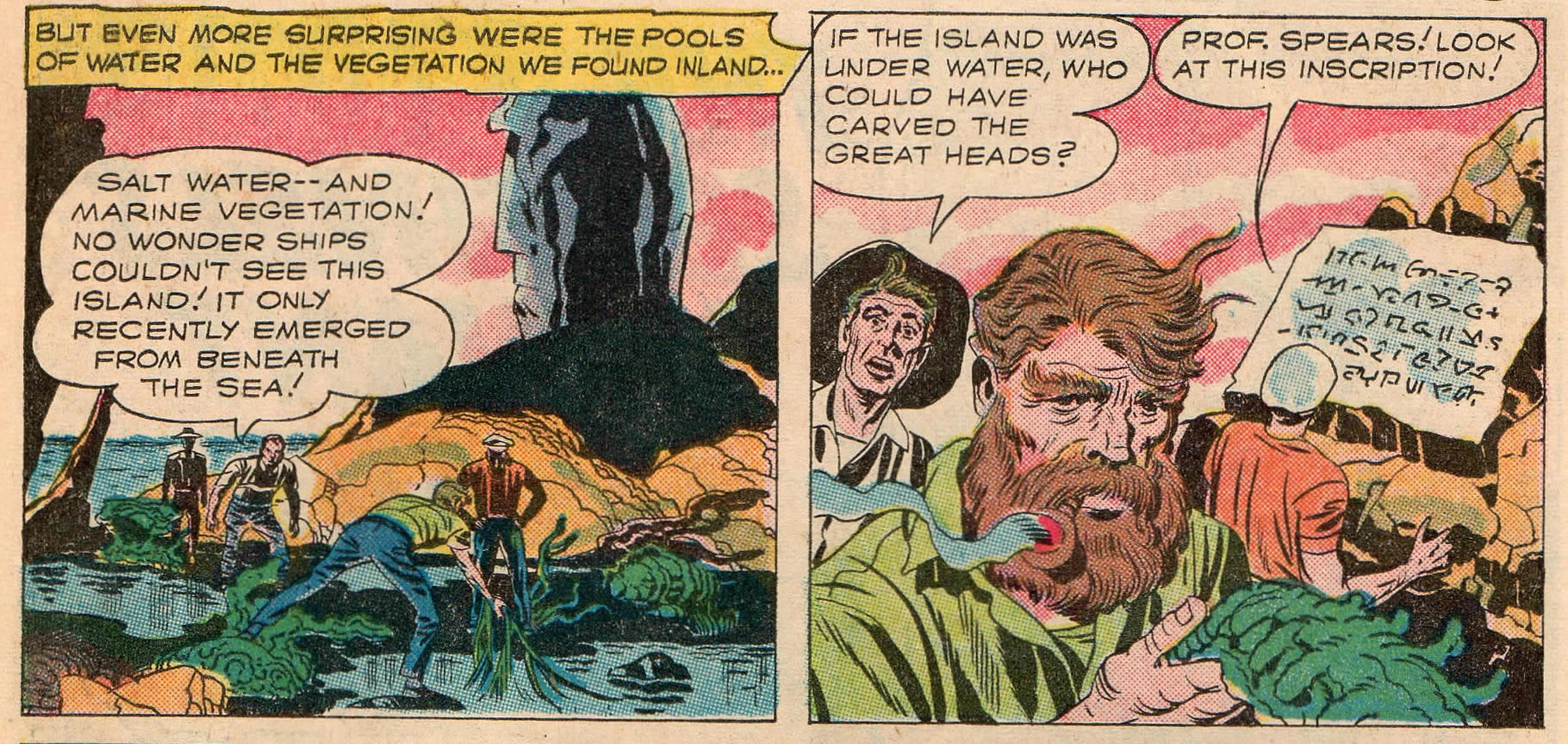

Rongorongo in Comic Books

Lais und Ben 1 (Comic Art: Hamburg, 1990) |

|

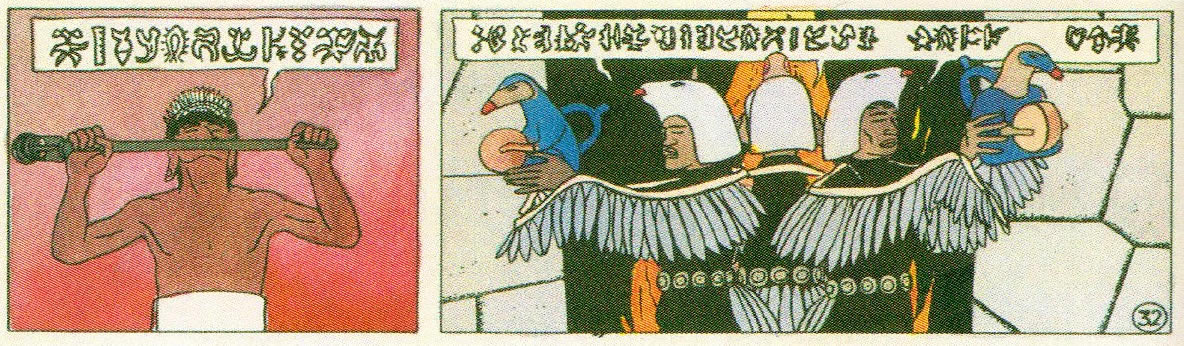

Considering that rongorongo is not widely known, comics depicting moai often weave the glyphs into the story, where they are discovered as an arcane language inscribed into architecture, at the base of the statues, or as tablets found around the island. The inscriptions act as a key to activate the moai, or a piece of alien technology. They can also function as a strange spoken language drawn in speech bubbles, for example in the German comic Lais und Ben, reviewed here. The rendition of the glyphs range from the abstract to accurate, showing that some artists must have had access to photographic material, even though research was minimal at the time. The truest representation of the glyphs is found in the Belgian comic Bob Morane: Les Géants du Mu [Bob Morane: The Giants of Mu], where they appear as a design on a cave column, the remnants of a sophisticated lost civilisation. |

|

House of Mystery, no. 85 (April 1959), DC Comics |

|

Despite the fact that rongorongo remains undeciphered, the glyphs in the comic books are often translated in a matter of minutes (or seconds if you are Captain Marvel) by the hero, or a companion - such as a bearded academic. The decipherment reveals a message from a doomed civilisation reaching out to humanity. Equally common is the theme of an alien race warning humanity to change its ways or face self-annihilation, or that the visitors will return some day upon fulfilment of an ancient prophecy. Martyn Harris Jump to contents |

|

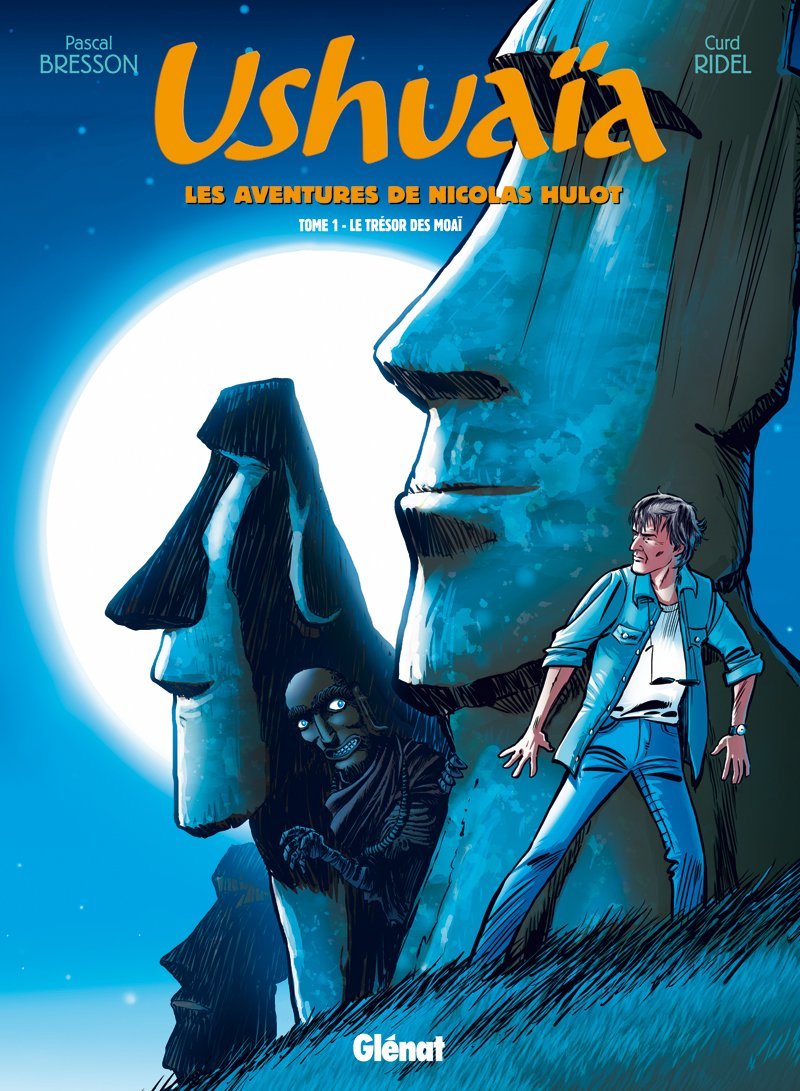

Makemake and moai kavakava

Ushuaïa: Les Aventures de Nicolas Hulot, Tome 1 - Le Trésor des Moaï, Whilst the moai dominate the landscape of Easter Island, as well as the myths and the popular images, there are other powerful carvings that are a significant part of the local culture. These include the Easter Island supreme god, Makemake, and moai kavakava, a haunting figure who initially appeared in spirit form to a king. Ian Conrich Jump to contents |

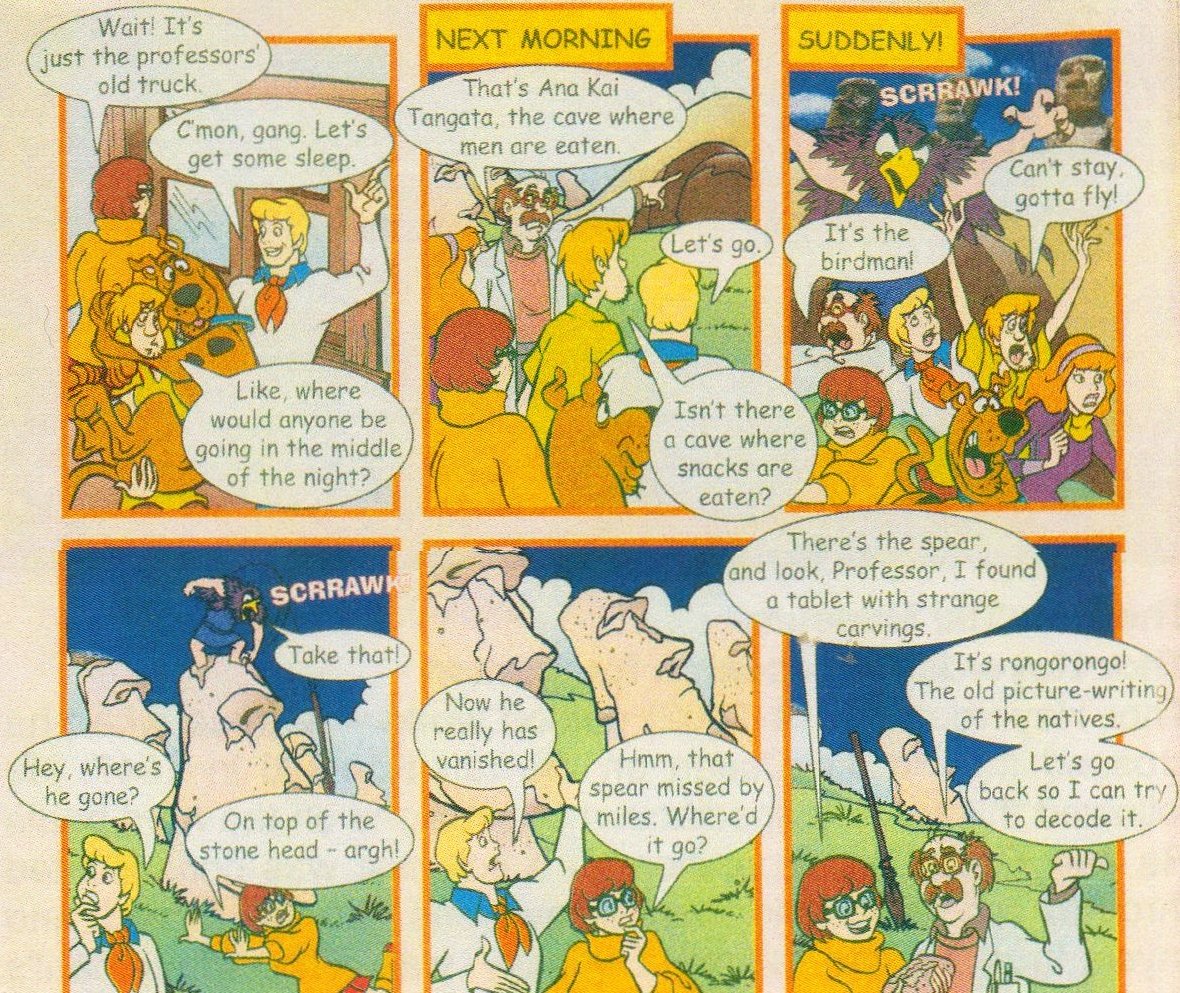

The Birdman Cult

Motif of the birdman (manu tangata), wooden carving with eyes made of shells, bought on Easter Island in 2003.

Scooby Doo! World of Mystery, no.26 (2005), De Agostini UK. |

|

It is believed that towards the end of the period of moai construction on Easter Island, the cult of the birdman (tangata manu) emerged as a new force in establishing social and political order. With a broken ecosystem brought about by the severe loss of forestry, whoever was crowned birdman each year had the power to control elements of the remaining food stock on the island. Just off Easter Island are three islets, the largest of which is Motu Nui (translated as Big Island), where each spring the sooty tern (manu tara) would nest. At a south-western point of Easter Island near to Motu Nui is a clifftop site called Orongo, where selected servants or warriors would prepare for the birdman race. This extreme competition involved climbing down a steep cliff, and swimming across shark-infested waters to Motu Nui, where the speckled egg of the sooty tern was sought. The first warrior to locate an egg intact, would announce his victory from a rock called the Bird's Cry and return to present the egg to his chief, who would be proclaimed the new birdman for the year and viewed as a man-god. With the arrival of missionaries who discouraged the practice, the last birdman was proclaimed in either 1866 or 1867.

Ian Conrich |